Our Freedom’s Price

- Nando Miranda

- Jul 18, 2020

- 6 min read

Written by Nando Miranda and published on May 23, 2015.

Dear Readers!

I had the distinct honor of interviewing retired art teacher and freelance author, Tuula A. of Turku, Finland. I visited her work studio and saw a piece that she had just completed. I was very impressed by the scale of her work and the importance of the subject matter – The Winter War. This year marks the 75th anniversary of Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union. The war lasted 105 days.

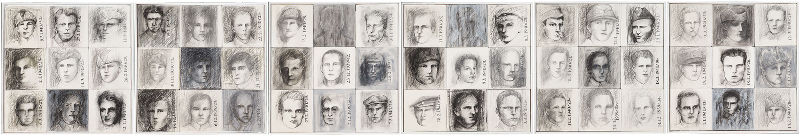

Here are a few photos of Tuula’s work entitled Our Freedom’s Price along with Q&A. Translated by Nando from the original Finnish language.

What is the name of this work of art? OUR FREEDOM’S PRICE. It is also the book’s name from which I drew the numerous soldiers’ faces. The book was published in 1941 and it lists the 30,000 fallen soldiers of the Winter War of 1939/40 with photographs and their information. When I was school aged, we didn’t live in Kerava yet nor did we have a library nearby, but I had found numerous stories in the books on the shelves of our home.

What was your inspiration?

During my childhood, these photos already affected me, each soldier’s face and their information of all those who had perished. I bought the same book at a flea market many years ago. I don’t know where the inspiration to draw their faces came from. Did it come from a new Russian threat or did these young soldiers want to give us all some kind of message? I felt during the entire process that they were grateful of my drawings of them. I went through waves of emotions when I drew their faces. They became very close to me.

How did you make it? Because I’m allergic to a few colors, I can’t paint, therefore I have to draw. I made the pictures by using a variety of techniques such as graphite, charcoal, wax, and pencils. Every picture is done on its own individual canvas as a base upon which I have added water color paper. They are then glued to cardboard and fastened into 90×90 cm squares. On the back is plywood for support and in front, plexiglass. Together there are fifty-four drawings, in six pieces with nine pictures each.

How did you choose the faces of the soldiers? By chance, always some faces stood out do to their better clarity. I increased their size on the computer where their facial expressions could be better seen. Lenses at that time were pretty good and the photographs withstood the enlargements. A large part of these photographs came from the soldiers’ own military IDs. I didn’t choose any smiling civilian photographs. Only head shots are shown in the book. Why are there no names attached to the faces? Some of the photos were recognizable in appearance, others not. I did not want my work to have different sizes thus I deliberately made each one uneven and different by shading in artificial ways. I did not want to use real names in the work, because they were meant to be displayed as partially anonymous. However, the date of death emphasized the fact that they were the real victims of the war.

I contacted the director of Kuvasto (Photograph Archives) and asked if it was legal for me to create drawings based on these public photos. Since the photographs were more than 70 years old and they would be connected to a work of value, there was no obstacle. I completed the work very quickly. I completed the work in one and a half months working 12-hour days. Did you lose any family members during the Winter War? In our family, luckily neither my mother’s or father’s family lost anyone in the war, but there were many family members who fought in it. My father Pauli’s high blood pressure kept him from the frontlines, but he worked in support services and in transportation. Of course, the war hurt Finland badly in a spiritual and physical way for many decades afterwards. Many men were traumatized for a long time because of their war experiences. Tragic memories haunted these men’s and their families’ lives. What do you remember about life after the war? Finland was in poverty and in trouble for many years. We had great losses, refugees from Karjala had to be relocated, war debts had to be repaid, and hard work was necessary. Children didn’t compare themselves with anyone, because we were all in the same situation, and they didn’t know any better. In our family, there was enough bread, because my father managed his brother’s farm until 1950. These times were full the entrepreneurial spirit, we invented a little, because everything was in short supply. Some of our elderly population still live today as then, collecting things and saving everything. On the other hand, a good sense of community was prevalent such as the desire to help others and a positive spirit towards the future. Small things were appreciated. I remember this time to be full of light and idealism based on good, strong values. How long have you created art? I have always drawn and painted, and took party in many culture competitions already as a child. I graduated from high school in 1963 and that same year went to Ateneum (Aalto University). I graduated as an art teacher in 1967 and afterwards it was mandatory to continue my studies at the university for art history and other subjects plus on-the-job teacher training. My studies lasted 6-7 years and food was always in short supply. There were no study loans. For home, I rented and money was gained from working over the summer and evenings. I was very appreciative of my entrepreneurial spirit.

How long were you an art teacher? I was an art teacher in many places. There was plenty of work on offer. Before Rauma I was in Kotka, Espoo and Nakkila. For family reasons, in 1974 I moved to Turku and here I’ve worked at different school and other places. I have worked at the art design school in Mynämäki, and lastly in Lieto. I’ve always had terrible allergies and in Lieto I became very ill. I left teaching work and the “moldy schools” in 1997. I taught 30 years from 1967-1997 in a variety of places.

When did you start writing? What did you write and for which magazines? I began writing periodic magazine articles in the 1980s. I also wrote children culture books and also stories for magazines Kotivinkki, Meidän Talo and ET-lehti. I have many stories about home décor, personal interviews and arts & crafts.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to become an artist or article writer? Gain as much knowledge as you can, keep your senses open, go to exhibits, read a lot, and also read magazine articles. Intuition is useful, as well has the ability to get inspired, and read the story behind the words. Respect your interviewees and your students, because they are your employers. Write beautifully. Get background information about your stories. Always give your interviewee a chance to read your story beforehand and to see the photos.

Where is Our Freedom’s Price being displayed? The work travelled with my son to Helsinki on March 13th after they were prepared the previous week. They were displayed in the lobby of the Laajasalo Church for their Winter War memorial concert that same Friday evening. At this event, the Kaaderi Choir sang, and one of the singers is a classmate of mine, Colonel Heikki Hult. He told me over the phone that there was great interest in the piece and its creator that evening.

The work was then shown at the Santahamina Soldier House (Sotilaskoti) where they were taken April 7th. From there they moved on to Laajasalo’s Degerö House where the local Lions Club asked them for their art show opening at the end of May.

It is interesting to see where they will move and where they will eventually stay. It is surprising how the soldier drawings are well talked about by viewers on many different levels. Also, for me as the artist.

(First published on May 23rd, 2015, at Nando's Notes website. From the Nando Miranda Archives located within the vaults of the Nando Miranda Museum of Natural History & Memorabilia.)

Comments